This entry is part of the #staythefuckhome series, all written during the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. In this series I’ve aimed to post about films that readers (at the time) can easily find and watch online. Keep yourself healthy and entertained.

Starting off, this is entry is the first time where I’ve done a second entry for a director in Film Klub; this director being Australia’s Peter Weir, of whom I’ve already covered his 1977 supernatural, apocalyptic mystery film The Last Wave a little while back. Released two years earlier, 1975’s Picnic At Hanging Rock is probably his best known film, and what I believe to be a classic Australian film as it combines a lot of features and themes from other well-known cinema from “down under” at the time: amazing cinematography, the country’s iconic landscapes and often a struggle between settlers from the new world and the strange environment they now live in that they don’t quite understand.

The film is based on a book by Australian novelist, playwright, essayist, and visual artist Joan Lindsay. The book was released in 1967, and by that time she had already a number of books over the course of a few decades. What makes this book and the resulting film engaging is that the mystery is never solved, making the story of this film burn in the back of one’s mind long after the last page is read and after the last set of credits roll.

Set in the year 1900, right around Valentine’s Day of the new century, the story of Picnic At Hanging Rock revolves around a group of young girls at a boarding school around Mount Macedon in the central Victoria region of Australia who go on an ill-fated trip to one of the area’s geological marvels, Hanging Rock — a strange geological formation in the area’s central plains.

The film’s enigmatic character lies in its contrast of hazy, period-piece splendour and the dark, menacing supernatural mystery that drives the plot. The film opens as the schoolgirls of Appleyard Academy start their day, preparing for a lovely, sunny picnic trip to Hanging Rock. There’s a lovely Art Nouveau or Aubrey Beardsley quality to these scenes, set to a very lush and pastoral soundtrack provided by Romanian pan-flautist Gheorghe Zamfir and Swiss organist Marcel Cellier. Long shots of the schoolgirls brushing their hair, tying their corsets, pressing flowers into books and preparing for their day trip, as well as the insight to the relationship of model student Miranda and the more shy Sara, who have a friendship that implies more than that.

“You must learn to love someone else apart from me, Sara. I won’t be here for much longer.”

With that bit of foreshadowing, the introductory atmosphere of the film is broken by the head schoolmistress, Ms. Appleyard (Rachel Roberts) who exerts a terse, Victorian authority over the girls underneath one of the more bizarre, memorable and out-dated hairstyles I’ve seen in period films. Appleyard outlines the rules of the girl’s trip to Hanging Rock (they’re even allowed to take off their gloves on the trip! Letting loose!) and when they are to return and then sets them on their way under the guidance of coachmaster Mr. Hussey, the esoteric mathematics teacher Miss McGraw (Vivean Grey) and the younger, jittery teacher Mademoiselle de Poitiers (Helen Morse).

As the girls head out to Hanging Rock, the film starts to slowly turn to a more abstract, dreamy quality and the atmosphere of mystery starts to creep in. From the strange conversations in the coach about time to the lush scenes of the girls picnicing at the foot of the landmark, there’s a lot of slow crossfades and shots that are of a more painterly quality, often invoking the lush 19th century landscape painters or the post-impressionism “pointilism” works of artists like Georges Seurat (especially his piece A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884).

During the picnic a phenomenon of “lost time” starts occuring. The pocketwatches of Mr Hussey and Miss McGraw stop working and that’s when the trip starts unravelling more into an even more vague dreamscape. The girls start napping and dreaming and from there a group of four girls, headed by Miranda, decide to go on an adventure to climb the rocks to the top, swept up in the romanticism of their day out.

As they start their climb, they are observed by another small party at a picnic, which includes a young upper-class, young Englishman Michael and the family’s young valet, a more rough-and-ready Australian by the name of Albert. The two boys have a friendship, despite their class differences that are pointed out often in the film, and they observe the girls as they climb the rocks, almost in a trance.

And as the climb progresses, the soundtrack duties hand off from Zamphir to Australian composer Bruce Smeaton’s pieces, which have a far more menacing, dark quality to them — dense drones with somber piano passages. It’s obvious the girls are getting lost, not only in the landscape but also in their minds. The strange power of hanging rock starts distorting time and the girls at several points lay down and start to drift off into the dreamscape. Edith, the less adventurous of the girls, starts to panic and tell the others they shouldn’t go any further and return back down back to the picnic. No-one is listening, and as the other girls start to remove their shoes and take off their stockings, they start to ascend even higher by instinct as the dialogue starts to get more and more sparse and the sense of time starts to get more and more abstract.

It all climaxes as Miranda and the other two girls start to ascend further without any reason or without any decision made. It’s a pretty chilly scene, all in slow motion and with their backs turned to the viewer just disappear behind the rocks. This haze is broken as Edith screams and starts to run down the mountain.

It’s interesting that the film’s main climax happens within the first half of the film. From there the carriage of girls returns back to Appleyard Academy in the dark of night with the remaining pupils and staff in a panic as they return. Miranda, and the two girls, along with the mysterious Miss McGraw have vanished with no trace. The stern Victorian veneer of schoolmistress Ms. Appleyard slowly starts to break down.

The remainder of the film revolves around the search efforts of the local authorities to find the girls, along with the the boys Michael and Albert teaming up together on their own rescue efforts as they scramble across the menacing landscape of Hanging Rock – almost succumbing to the same loss of time and sanity as the ill-fated schoolgirls they are seeking did. In the end they find one of the girls almost near death.

Things start to unravel. Parents of schoolgirls stop paying tuition due to the notoriety of the incident, Sara (whom has affections for Miranda earlier in the film) is threatened to be sent back to the orphanage and takes her own life and finally, without solving the mystery, it’s revealed in the ending credits that Ms. Appleyard in the impending closure of the school is found dead at the foot of Hanging Rock. No closure. Nothing is solved.

It’s quite rare for a film to have an open ending as such, and when the film came out distributors and those who had seen the first viewing were upset that the film had no closure, so much that one distributor threw a coffee cup at the screen “because he’d wasted two hours of his life—a mystery without a goddamn solution!”

When Joan Lindsey was writing the book, there was an original version with an extra chapter that explained the mystery, of supernatural origin, but in the end opted to leave it out. There’s even a lost ending to the film which almost attempts to wrap the story but doesn’t quite solve the mystery. I think this lack of conclusion is what makes this film extra special and will burn on many people’s minds long after viewing.

I have a bit of a soft spot for select period films and television, especially ones from Britain from 60s and 70s where emphasis is placed on dialogue, society and politics of the day. A good example of this would be the 1974 series The Pallisers, a 26-episode television serial released by the BBC in 1974 featuring a lot of established actors of the day: Susan Hampshire, Jeremy Irons, Anthony Andrews as well as Philip Latham, whom fans of Hammer Horror films would know as Klove, the man-servant of Christopher Lee’s vampire in Dracula: Prince of Darkness.

As for Picnic At Hanging Rock, I’ve always loved how the music ties in with the imagery of this film, balancing a fine line between organic, daydream beauty accented by the pan-flute pieces of Zamfir contrasted with the surreal, looming mysterious features of the rock where Bruce Smeaton’s more dirge-y atmospheric compositions throb with psychological frenzy. Years ago when I was composing tracks for the one-off, instrumental Soft Riot album Some More Terror, I think this track, “Momentary Lapse In A Crowd”, probably took a bit of influence from that.

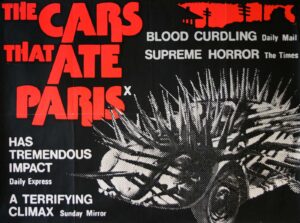

With two Peter Weir films now covered, it’s worth mentioning that his film The Cars That Ate Paris is definitely worth a watch as well. Released a year before in 1974, it’s a more aggressive film that’s a bit hard to explain, although it can be summarized (better than I can explain it) as “a film is set in the fictional town of Paris in which most of the inhabitants appear to be directly, or indirectly, involved in profiting from the results of car accidents”. I consider this film to be probably one of the first of the Australian “apocalypse” films (albeit without an actual apocalypse), mainly due to the rules of chaos and weirdness that dominate the town and of course, the iconic vehicle designs that definitely laid down the groundwork for films like Mad Max and all the imitation films that followed throughout the following decade.

With two Peter Weir films now covered, it’s worth mentioning that his film The Cars That Ate Paris is definitely worth a watch as well. Released a year before in 1974, it’s a more aggressive film that’s a bit hard to explain, although it can be summarized (better than I can explain it) as “a film is set in the fictional town of Paris in which most of the inhabitants appear to be directly, or indirectly, involved in profiting from the results of car accidents”. I consider this film to be probably one of the first of the Australian “apocalypse” films (albeit without an actual apocalypse), mainly due to the rules of chaos and weirdness that dominate the town and of course, the iconic vehicle designs that definitely laid down the groundwork for films like Mad Max and all the imitation films that followed throughout the following decade.

I’ve sampled both Picnic At Hanging Rock and The Cars That Ate Paris for use in live shows over the years, and the latter was quite a prominent influence of a track of an old band I was in when living in London. Perhaps a mix of influence of this film mashed up with J.G. Ballard‘s book Crash. The title of the film is even mentioned in the track’s strange, colourful and psychedelic lyrics, courtesy of lyricist/singer Del Jae:

And yes, you can watch that film online as well (see below).

If you enjoyed this film, it might be worth checking out Morgiana and anything by Peter Greenaway, including A Zed And Two Noughts which I’ve covered both in Film Klub as well.

Videos

Original Trailer

Soundtrack Excerpt

Full Film on YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ueVib29wg0

The Cars That Ate Paris (Full)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OuKpHuFqZhQ